Growing Old in a New Town: 15-minute Cities, Loneliness and Elderly People’s Mobility

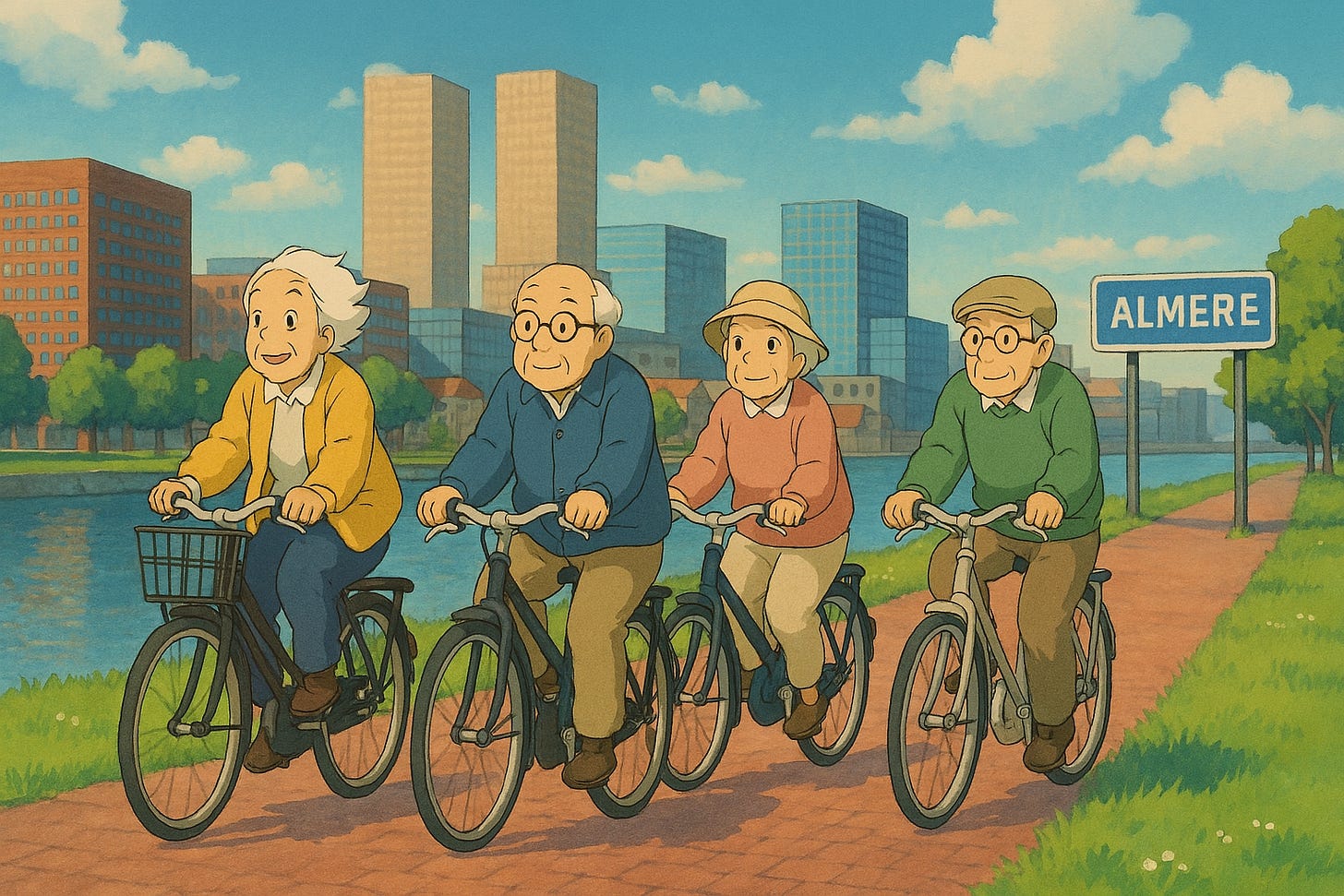

Perspectives | 15-minute Cities | Almere, Netherlands

If you were to walk in a European city 600 years ago, you would probably marvel at the sheer amount of children on the streets, playing, running, maybe even working. On the contrary, if you time-traveled to the same city in 2050, one of the first differences you would notice is the large number of elderly people walking, shopping, or sitting at cafes’.

Changing age demographics in Europe are presenting cities with an unknown challenge: how to adapt urban spaces to the growing number of elderly people? Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the global population over 60 years old is expected to nearly double, from 12% to 22% (WHO, 2024). And with aging, come challenges that can be improved or worsened by urban spaces, raising questions about how to best accommodate the mobility needs of an aging population.

For my master’s thesis, I decided to embark on a research project on the 15-minute city in Almere, supported by Hogeschool Windesheim and the University of Amsterdam. One of the peculiarities of Almere is its polycentric structure, ideal to facilitate the creation of 15-minute city neighborhoods, where anyone can reach their destination within a short walk or bike ride.

However, Almere is also a city where 50 years ago, everyone was young, since it was built in the 1970s, together with the whole province of Flevoland, to accommodate young families and commuters. Where once there was only water, suddenly there were cities, villages, and roads. And so, on the 1st of December 1975, the first pioneers of Almere opened the doors to their brand new houses, preceding the tens of thousands of people that would follow them. Soon after, Almere became the fastest-growing city in the country, counting over 200,000 inhabitants today.

Now, in 2025, those first inhabitants are old and are enjoying their well-deserved retirement. However, the city which was primarily inhabited by 'young' people for most of its history, now faces a rapid increase in the number of elderly.

As I approached the case study of Almere, I was fascinated by this peculiarity, and once I started reading literature on the 15-Minute City, I realized that not much was written about the existence and needs of elderly people within this urban planning model.

An idea, a research.

The 15-minute city, thanks to its focus on proximity, has the potential to reduce car centricity, improve social cohesion, and create stronger and more resilient communities. However, not all distances are created equal, and a 15-minute walk for a young student might be a 40-minute walk for a 70-year-old woman who just had a hip replacement. Being able to reach destinations is extremely important for human beings; as Aristotle wrote, humans are social animals, and our well-being is heavily dependent on social interactions. Especially for older adults, who are retired and often live alone, being able to move outside of their house means meeting others, maintaining contact with the world, and keeping a healthy mind and body. Even brief and casual encounters on the road can increase the possibility of engagement with other people from all walks of life, and help reduce loneliness, preventing mental health issues.

This is what particularly interested me: understanding the 15-minute city in relation to the mental-well being of elderly people and especially its potential to reduce loneliness. My research question was: In what ways can the 15-minute city concept serve as an effective framework to reduce loneliness among elderly residents of Almere Buiten1?

The research process

To conduct my thesis research, I interviewed 19 people between older adults and care workers, to understand the mobility challenges of the neighborhood, how these challenges impacted loneliness, and how a 15-minute city could enhance liveability by tackling the relationship between mobility and loneliness. In addition, I engaged with unstructured observation and desk research to gain more insights into the current situation.

Analysis

Interviewing elderly people was an interesting experience that challenged my preconceptions of old age. Talking to them, and especially to a crocheting group of elderly ladies that meets weekly in a community center, revealed to me many aspects of their mobility patterns:

Being able to go out is extremely important for elderly people. Spending time outside is an activity they look forward to, just as much as being able to go to the neighborhood center to participate in crochet clubs, play bingo, or just stop for a coffee.

Distance is a relevant challenge for many, which would be easier to deal with if there were more benches to stop along the way

Weather is another important factor, when it rains, it snows or it is too hot, it can be dangerous for elderly people to walk or cycle, meaning that they will either drive (those who still can) or stay at home.

Mobility represents a key to freedom and independence. For some elderly people, especially those who struggled with walking, the car was a necessity; while for others the (e-) bike was most important, as it helped with cycling against the wind and on bridges.

From the interviews, it also emerged that loneliness was a big issue and worry. A few of the interviewees had spent their life working in Amsterdam, the city they came from and where they had built their whole social network; however, once they became old and couldn't go to Amsterdam as often, they realized they had not made enough meaningful connections in their neighborhood in Almere. Moreover, many lived alone due to the passing of a spouse, facing loneliness and mental health problems. The interviewees did not mention their loneliness directly, but rather circled around it, often using other people’s as examples. I find this quote particularly meaningful:

“Many people live alone, and sitting home alone makes you feel sad, especially if you have lost your partner; then it is better to be outside, to sit somewhere and talk to other people, hear other people’s stories, laugh a little, play a little game, cry if necessary... It is more fun... When you sit at home, you have a loneliness that comes over you and then you collapse, it makes you sick, so a community center, it is the ideal place for (elderly) people” (quote from an elderly man volunteering at a neighborhood center).

This research was impactful for me, also on a personal level, as it was not always easy to hear stories of loneliness. Two women I interviewed were particularly nostalgic about the public transportation network in Amsterdam and missed hopping on a tram to go to de Dappermarkt like they used to do in their youth. Another woman expressed her disappointment at not knowing her new neighbors, who never stopped to talk to her, and joyfully remembered the previous ones, who let their cat sit on her lap. Hearing these stories, and also listening to the worries of care workers who see loneliness as a major problem for elderly people, triggered a lot of reflection on the role of planning for proximity.

Although Almere Buiten is a neighborhood built on a proximity model, elderly people struggle with moving through it and often feel embarrassed asking for help. In addition, they often don’t know their neighbors, and wish they could meet more people.

Struggling with walking, biking, and driving poses a significant challenge for the future due to the potential increase of difficulties for their mental and physical health. The structure of the neighborhood also does not help in fostering strong social ties, which could be due to the suburban housing style, the commuting nature of Almere’s residents, who mostly work outside of the city, or the difficulty in building social connections in a new town. In addition, the proximity structure of Almere is built on the idea of a young person's mobility, someone who can walk, cycle, or drive without difficulty.

For this reason, when discussing the 15-minute city model, it is important to ask ourselves who these 15 minutes are for. Perhaps, future planning models could focus on the entity of the street and on how to create networks of connections and mutual aid between neighbors. One important limitation of this research is that it could not reach those who live at home and cannot go out, due to relevant physical problems. The number of people with such difficulties will also increase in the future, and planning models need to take this into account by focusing on enhancing social cohesion and neighborhood ties. Elderly people are a cornerstone of society, they are keepers of memories and history, and they deserve to live in a city capable of accommodating their wish for independence and diverse social interactions.

Almere and the bike

While my research did not directly address the role of the bike in the mobility of elderly people, the importance of pedaling emerged throughout the interviews. Older adults, especially in the Netherlands, enjoy riding bikes and wish to do so for as long as they can. A complaint that is often brought up when talking about cycling in Almere, is the structure of the cycle lanes: long, monotone, crossing open stretches of green spaces. This does not facilitate cycling for elderly people because on such a cycle lane it is often more windy, and the isolation of the cyclist is also a relevant factor, as it is difficult to meet people or to stop and sit on a bench.

The cycle lanes of Almere are built with efficiency as the primary goal, ignoring the importance of play, social interaction, and social safety. Perhaps, it is time to change our paradigm and embrace new criteria for cycle lanes, here are some suggested ones:

Number of cats that can be pet along a route

Amount of different species of flowers that can be recognized

Comfortable benches to sit and chat (bonus if this can be done while petting a neighborhood cat)

Number of people to say hello to

Different street art to admire

What else?

Written by

, Researcher at Urban Cycling InstituteInterested in writing or sponsoring an article? Send us a pitch at media@urbancyclinginstitute.org

Learn More:

From our research:

Sources

Allam, Z., Moreno, C., Chabaud, D., Pratlong, F., “Proximity Based planning and the 15-minute city: A sustainable model for the city of the future”

Ageing and Health, WHO Ageing and health

Te Brömmelstroet, M. Nikolaeva, A., Glaser, M., Morten., N., Chan, C. (2017) “Travelling together alone and alone together: mobility and potential exposure to diversity”, Applied Mobilities, 2:1, 1-15, DOI: 10.1080/23800127.2017.128312

Sundström A, Adolfsson AN, Nordin M, Adolfsson R. (2020) “Loneliness Increases the Risk of All-Cause Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease.” J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 16;75(5):919- 926. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz139. PMID: 31676909; PMCID: PMC7161366.

Rishbeth C, Rogaly B. (2018) “ Sitting outside: Conviviality, self-care and the design of benches in urban public space.” Trans Inst Br Geogr.; 43: 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12212

Pozoukidou,G.; Chatziyiannaki, (2021) Z. “15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia.” Sustainability, 13, 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/ su13020928

Mollenkopf H, Marcellini F, Ruoppila I, Széman Z, Tacken M, Wahl HW. (2004) “Social and behavioural science perspectives on out-of-home mobility in later life: findings from the European project MOBILATE”. Eur J Ageing.;1(1):45-53. doi: 10.1007/s10433-004-0004-3. Epub 2004 Nov 5. PMID: 28794701; PMCID: PMC5502681.

Matsuda, N., Murata, S,. Torizawa, K,. Isa, T,. Ebina, A,. Kondo, Y,. Tsuboi, Y,. Fukuta, A., Okumura, M., Shigemoto, C., Ono R., (2019) “Association Between Public Transportation Use and Loneliness Among Urban Elderly People Who Stop Driving”. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 13;5:2333721419851293. doi: 10.1177/2333721419851293. PMID: 31321253; PMCID: PMC6628514.

Bevolking Data, Almere in Cijfers, 2023. Almere in Cijfers - Gemeente Almere

Almere Buiten, one of the city’s neighborhoods, was chosen because of its structure and the proximity of amenities to houses. In addition, the 15-Minute city research project was happening in this area, facilitating the construction of a network and comparison with my classmates' work.

Hi Michela. 15 or 20 minute cities as a term has become a trigger term on the right because of the view there that you won't be able to get outside of your 15 or 20 minute city. This is not something that can be dismissed easily as it was at play in places like Melbourne (where I seem to have ended up living somehow) during COVID.

I wish I was less able to empathize with the loneliness of getting older when you're single as well. But these things happen.