In the celebration of Native American Heritage Month, we dedicate our Friday cycling news to a special story by Michael Tahmoressi. Michael is a communication studies researcher and a PhD fellow at the Urban Cycling Institute. For the past year and a half, he has been researching bicycle repair communities in the Netherlands and the reciprocal bicycle and human relationship. Read on to learn about Michael’s approach to his work with bicycles, reflecting the values of his indigenous heritage.

I look back on this experience now as my first real exposure to Indigenous relationality as a worldview. At the Powwow, they would open with a thanksgiving which would honor the living world, plants and animals, and the land that sustains them.

Growing up, my uncle would take me and my cousins to Austin, Texas, Powwow. We would watch people from around the state and region dance traditional dances. He would tell us stories of my grandfather growing up on communal land in Michoacán, Mexico. Through my grandfather, I am Purépecha, the group indigenous to Michoacán. My cousins and I were never allowed to go to this land. By the time we were old enough, Michoacán had been engulfed in cartel violence. This is why my uncle insisted to my mom that my sister and I should attend the Powwow every year. It was one of the only ways we could be connected to a culture that we had been separated from, even though we were not directly related to the people who were dancing at the Austin Powwow. I look back on this experience now as my first real exposure to Indigenous relationality as a worldview. At the Powwow, they would open with a thanksgiving which would honor the living world, plants and animals, and the land that sustains them. This thanksgiving would remind us of our own place within this system as stewards who live alongside these living elements that sustain us.

Indigenous relationality was always present in my family's celebration of Dia de los Muertos. Dia de los Muertos is rooted in the Purépecha mythology. People in Michoacán will return to the gravesites of their family members and hold vigil on November 1 and 2. Our ancestors return on this night and we are able to commune with them through remembering. Growing up, we would build altars at mis abuelo's houses, with pictures of tios, tias, y los abuelos de mi mama y su hermanos. Since my grandparents and aunt of my mom and her brothers passed, we honored them on the altar now alongside our older relatives. Dia De los Muertos is an opportunity to give thanks for the life that came before. We let our ancestors know that we appreciate the protection they offer us from the spiritual world.

The concept of animacy, or giving agency to nonhumans, allows me to theorize how bikes can speak to their riders.

One of the main ways I honor my indigenous heritage is by utilizing indigenous theory as a primary method to research cycling. In my work, I look at ways to teach people to adopt a more reciprocal relationship with the world around them. This is why I research bicycle kitchens because they teach people to have a reciprocal relationship with their bicycles. The concept of animacy, or giving agency to nonhumans, allows me to theorize how bikes can speak to their riders. Robin Kimmerer, a Potawatomi botanist and author of Braiding Sweetgrass, describes how her language, Potawatomi, is 70 percent verbs and 30 percent nouns (Kimmerer, 2017). For Kimmerer, the language being verb-based is a way to account for the Potawatomi worldview that views the natural world as a vital partner that sustains human life.

“In Potawatomi, rocks are animate, as are mountains and water and fire and places. Beings that are imbued with spirit, our sacred medicines, our songs, drums, and even stories, are all animate. The list of the inanimate seems to be smaller, filled with objects that are made by people. Of an inanimate being, like a table, we say, “What is it?” Moreover, we answer Dopwen yew. Table it is. But of an apple, we must say, “Who is that being?” And reply Mshimin yawe. Apple that being is” (Kimmerer 2017 p.g. 56).

I think that (being able to maintain ones own bike) is an issue of social justice and it is also necessary for cycling to be a sustainable agent of urban transformation.

I want my work to help people understand the need to take on a relationality that sees the natural world and the tools of our lives as reciprocal agents. I believe that everybody should be able to maintain their own bikes. I think this is an issue of social justice and it is also necessary for cycling to be a sustainable agent of urban transformation. Every year the city of Amsterdam removes 350,000 bicycles from the streets and takes them to the fiets depot (Ministerie I&W, 2023). Only 100,000 of those bicycles are ever picked up by their owners (Ministerie I&W, 2023). That means over 2/3s of the bicycles removed from the street end up abandoned.

My work helps us to understand the bicycle’s animacy. I think understanding the bicycle agencies can give us a viewpoint on how to help people have better relationships with their bicycles. The bicycle has been theorized as being a convivial tool (Illich, 1973). A convivial tool is one that a person can easily use and maintain (Illich, 1973). Illich believes that these types of tools grant people freedom from having to rely on the market for essential elements of their lives.

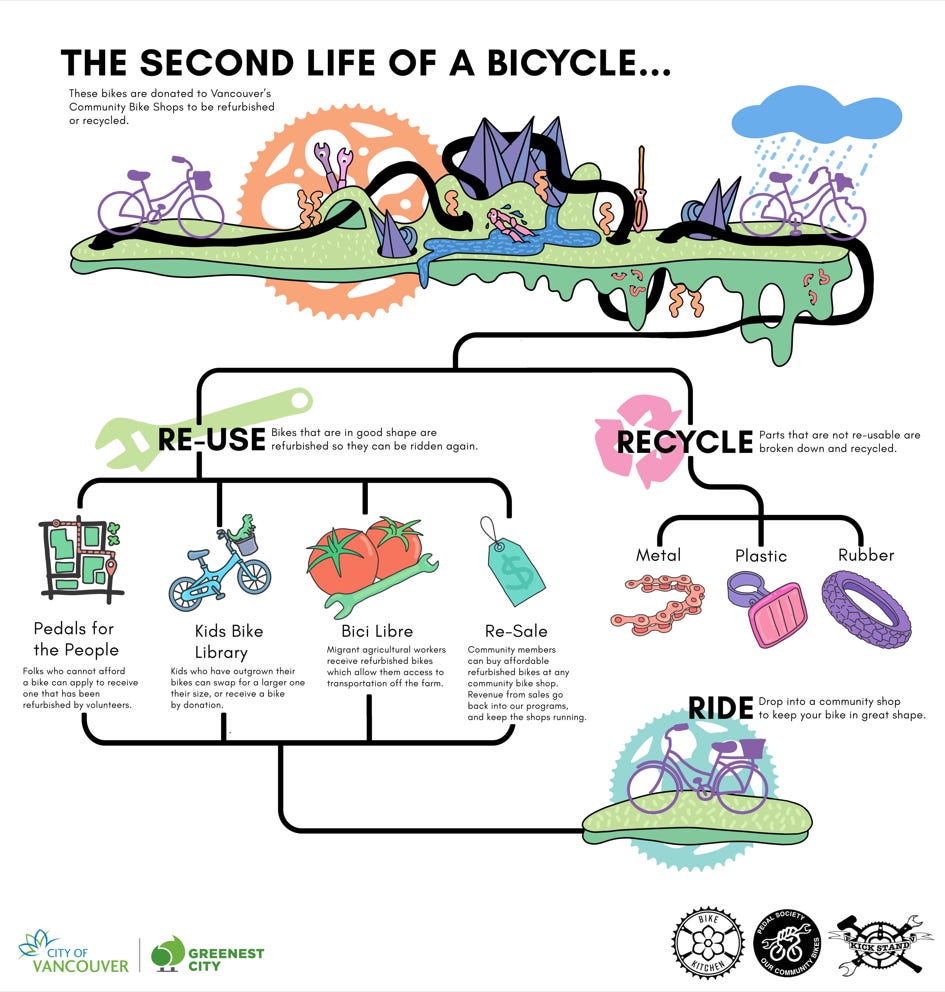

One of the main ways that bicycles talk is by telling people when they need maintenance. One way I have observed this take place is when Romee Nicolai, the leader of Bike Kitchen at University of Amsterdam, said, “People show up to the bike kitchen because their bikes are screaming at them.” The bike’s screaming is the noise it is making because a part has worn past its ability to function. The bike is asking its human compatriots to reciprocate the care that it gives to the person. Bike kitchens are places where people learn to listen to their bikes. Through learning to look and listen for problems and solutions to these problems, they gain skills to be better reciprocal partners to their bicycles. This image maps out the way bicycle and human relationships can be circular. It demonstrates how the material conditions for reusing bikes are already in place. What needs to happen now is for people to accept responsibility and take care of their bicycles.

Inspiration & Resources

The Bike Kitchen resources

Bike program that teaches bicycle maintenance to Latinx and indigenous children in New Mexico

Native women ride on Instagram

BYCS: Mobility as a human right amendment which was adopted as part of the constitution in Mexico

People for Bikes: Ride for gratitude and the Navajo nation

References

Kimmerer, R. W. (2015). Braiding sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions.

Illich, I. (1973). Tools for Conviviality. (New York: Harper and Row)

Ministerie, I&W. (2023). Meer achtergelaten fietsen krijgen voortaan nieuwe eigenaar. Accessed online at Meer achtergelaten fietsen krijgen voortaan nieuwe eigenaar | Nieuws IenW

If you would like to learn more about Michael Tahmoressi’s research, connect on Linkedin.

Sounds crazy at the beginning but it makes sense after reading! Thanks